The article articulates basic information and debunks some misconceptions about ‘Matabeleland’ or ‘Mthwakazi’. Note: the names Matabeleland and Mthwakazi are themselves a source of local controversy – to be explained later. In this article the names are interchanged to refer to the territory once ruled by King Mambo and King Mzilikazi – a territory made up of contemporary Matabeleland extending to parts of the Midlands region. It is home to black Africans and a small population of people from non-African background (e.g., Europeans and Asians).

Matabeleland and Midlands

IS IT Mthwakazi or Matabeleland?

Place names portray history, identity, culture, religion, and more importantly they imply control. For that reason, naming our territory remains a source of intense debate. Some Kalanga scholars reject the name Mthwakazi; this may be a well-orchestrated reconstruction of history and deliberate politicisation of the name to justify the view of its supposed socio-political toxicity. These academics tend to be receptive to Matabeleland which they view as more reflective of our society as opposed to Mthwakazi; they argue rather unconvincingly that Mthwakazi is a perpetuation of Nguni hegemony and an attempt at assimilating other population groups in the region. Significantly, they dispute the historical existence of a viable Mthwakazi state arguing Mthwakazi is a region in Matabeleland and specifically a territory occupied by Nguni ethnic groups.

Origins of the name Mthwakazi

The origin of the name Mthwakazi is contestable among local historians. One argument is that it was King Mzilikazi who named the territory Mthwakazi in honour of the first group of people (AbaThwa) to occupy the land. It is argued that the name is a derivative of the name of Queen Mu-Thwa the first known ruler of the territory who ruled around 7,000 years ago. She was the matriarch of the AbaThwa (Figs. 2), the San people often referred to in the derogatory term ‘Bushmen’ by European scholars.

Why the name Mthwakazi causes political tension

After an investment in renaming Bulawayo streets and avenues in Shona political, cultural and historically significant symbols/ figures, it comes as no surprise that those in control of Zimbabwean political power will resist the rejuvenation of the name Mthwakazi hence the idea of Mthwakazi statehood. After all, place-names are not just names, they convey a message about geopolitical power and control.

The process of naming places involves a contested identity politics of people and place; place names are part of the social construction of space and the symbolic construction of meanings about place. The name Mthwakazi is essential in the construction of the symbolic and material orders that legitimise the territorial dominance of the Ndebele nation. Attempts by Mthwakazi nationals to rename (and in the process reclaim) Matabeleland and parts of the midland’s territory is disruptive to Harare’s standing goal of imposing one identity in the modern state called Zimbabwe.

Disquiet over the use of the name Mthwakazi is based on the perceived and real threat of its political connotations to the people of the region. In a desperate attempt to distract the public from reality, the unitary Zimbabwe proponents use mainstream media to mischaracterise the name into an anti-Shona and Ndebele supremacist symbol. The name Mthwakazi is not a threat to unity or coexistence of the Ndebele and Shona people; discrimination and the resultant inequality is.

Zimbabwe State attempts to vaporize Mthwakazi

The focus of Zimbabwean propaganda is not only to misinform or push a Mashonaland agenda, it is also to exhaust people’s critical thinking with the objective of annihilating the truth. We notice too that apart from the name Mthwakazi, calling for a change of Lobengula Street to its historically significant form King Lobengula Road and calls for the replacement of Leopold Takawira Avenue with King Mzilikazi Avenue cause unease within a largely Mashonaland biased Zimbabwe government.

Renaming calls have been deliberately given a negative connotation within the mainstream media that has conveniently turned such calls into some form of Ndebele nationalism and an anti-Zimbabwe pursuit, yet it is common knowledge that Mthwakazi is a formal and well-known geopolitical name for the traditional nation-state founded by King Mzilikazi in the 19th Century. And Lobengula was not just another man, he was the King.

Explaining Mthwakazi statehood

We are presenting the past in its rightful context. Matabeleland’s statehood is not in question, a fact reaffirmed in a 2007 letter to Britain Ambassador in Harare as a ‘Notice of intent to file an application for the review of the verdict of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in the Land Case Matabeleland on the 19th of 1918’ by the late son and hero of Mthwakazi, former Governor and Resident Minister of Matabeleland North, the Honourable Welshman Mabhena, cited by Ndlovu-Gatsheni (2009):

Your excellence you may be surprised to hear that I usually get lost when…people…mix up my country Matabeleland with Zimbabwe, because Zimbabwe is a former British Colony which was colonised in 1890 and granted independence on 18 April 1980. While my homeland Matabeleland is a territory which was an independent Kingdom until it was invaded by the British South Africa Company (BSA Co) on 4 November 1893, in defiance of the authority of Her Majesty Queen Victoria. Actually, in terms of the Moffat Treaty of Peace and Unity of 11 February 1888 between Queen Victoria and King Lobengula, Britain and Matabeleland were allies, and due to our respect to our late King we have not renounced his vow.

Welshman Mabhena

Traditional borders of Mthwakazi

We refer to Sir Leander Jameson who, through his mapping, determined the influence of Matabeleland Kingdom to Umnyati River (Fig. 2) to the east, thus the Jameson line; while the names and borders of proposed states (Fig. 3 and Fig. 4) may be a source of contention among different Mthwakazi population groups, that of itself does not begin to invalidate Mthwakazi statehood.

Mthwakazi demographics

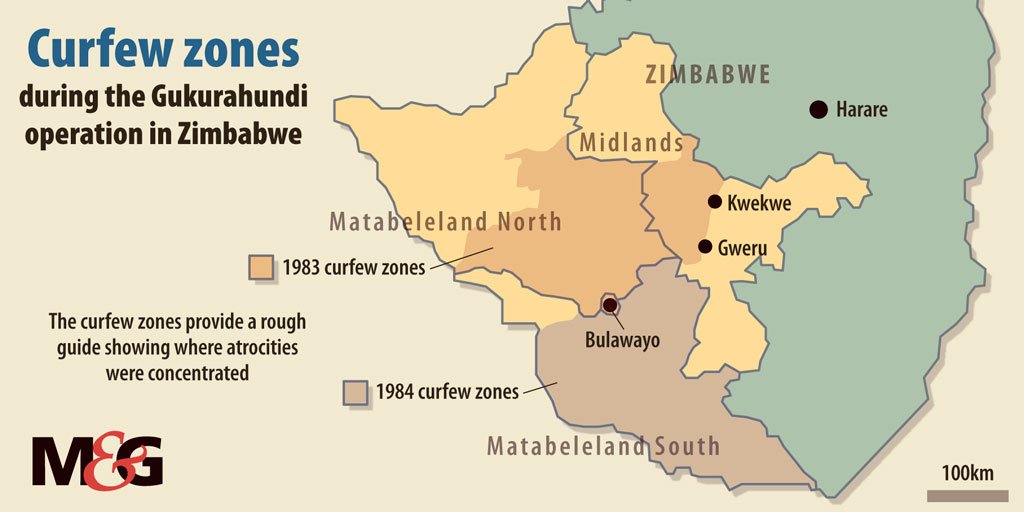

A comprehensive discussion of Mthwakazi demographics is impossible without a detailed data of the Midlands region; however, we will focus on the population of modern-day Matabeleland divided into three provinces: Matabeleland North, Matabeleland South and Bulawayo, the capital of the region.

Population groups who inhabit Matabeleland include the Kalanga, Nguni, Sotho, Tonga, Venda among others. As pointed out in the introduction, there are non-Black citizens who include those of European and Asian descent.

The Matabeleland region makes at least 17 percent of the human population of Zimbabwe. As of August 2012, according to the Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency or ZIMSTAT, the region had a combined population size of 2,086,247 in a surface of area of just over 130,000 km².

Matabeleland South’s population was 683 893 people, of whom 326 697 were males and 356 926 were females, and Matabeleland North province had a total population of 749 017 people. The sex ratio (proportion of male and female population) was 48 and 52 percent, respectively, within an area of just over 75,017 km². Last but not least, in the same census, Bulawayo province had a population of 653,337 in an area of 1,706.8 km².

Climate and economic activity

With significantly lower rains and frequent droughts (Fig. 6) thus, food and water scarcity, the region is naturally less hospitable to human habitation. Although the land is fertile, the dry climate makes large-scale crop production less viable for traditional farmers. The colonial government formed large numbers of cattle ranches, and cattle ranching has proven to be more successful than growing crops in the province. The mighty Zambezi River provides perhaps the best hope for a long-term solution to water problems in Matabeleland.

However, Zimbabwe government plans to draw water from the Zambezi River to the region via the conveniently named project Matabeleland Zambezi Water Project have stalled rendering large-scale crop farming and industrial growth ineffective since the 1980 ‘independence’.

Matabeleland North is also host to significant reserves of economically viable natural resources like gold, limestone, methane gas, coal, and timber. As evidenced in Hwange National Park (Figs. 7 and 8), a mammoth game reserve with a substantial wildlife population.

The most famous geographic feature of Matabeleland North is undoubtedly the Victoria Falls (Fig. 8), the world’s largest waterfalls, located on the Zambezi river on the northern border of the province.

Established as a tourist resort in 1953 and declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2003, the Matobo Hills or Matopos lies 35 km south of the city of Bulawayo, the Matopos consist of a broken and ancient, rocky landscape with a unique natural and social heritage (Figs. 11 – 12).

The Matopos area has one of the highest concentrations of prehistoric rock paintings (Figs. 13 and 14) in Southern Africa.

There is demonstrable, almost uninterrupted, association between people and the environment over several centuries. Through this interaction, one of the most outstanding rock art (Fig. 14) collections in southern Africa has resulted; the same interaction has also fostered strong religious beliefs which still play a major role in contemporary local society.

Arguably, the Matopos has one of the highest concentrations of rock art in Southern Africa dating back at least 13,000 years. The paintings illustrate evolving artistic styles and also socio-religious beliefs. There is ample evidence from archaeology and from the rock paintings at Matopos that indicates the Matopos have been occupied over a period of at least 500,000 years.

Matopos is an important feature in the history of Zimbabwe; it is central to many fundamental historical events that are of immense value to the modern nation of Zimbabwe. Of note are battle sites, graves, ruins and relics that date back thousands of years through to recent events.

Lying 22km west of the city of Bulawayo are the Khami ruins (Fig. 15), one of the major features of archaeological interest in Matabeleland South. It is a ruined city built of stones that dates back to the mid-16th Century following the abandonment of the capital of Great Zimbabwe.

Khami ruins, a national monument accredited a UNESCO World Heritage Site status in 1986, was once the capital of the Kalanga Kingdom of Butwa of the Tolwa dynasty. The discovery of objects from Europe and China on the site is evidence of Khami’s significant role as one of the major trade centres of its time.

Conclusion

Matabeleland is an ethnically and culturally diverse historic state founded in the 19th Century by King Mzilikazi on the southwest of present day Zimbabwe. Unfortunately, it has struggled for equal recognition and development in a colonially forced merger with Mashonaland to create the modern state of Zimbabwe. The prevailing politics of Zimbabwe’s interest is the protection of ethnic Shona interest, and its focus is the management of Mthwakazi, not its empowerment. As a consequence of ZANU PF’s Mthwakazi suppression agenda and insatiable appetite for a centralised government system, the territory has failed to reach its full economic potential to the detriment of the local economy, job and income security.

You must be logged in to post a comment.